Many Argentinian economists seem to believe, or say they believe, that if the country is dollarized, the people will leave the banks empty because they will take their dollars abroad, as they have done traditionally and keep on doing up to this moment. But people don’t do it because they don’t trust the dollars but because they trust them and do not trust the pesos. So, they prefer to hold their wealth in dollars rather than in pesos, and, given the bad experience they have had with the government’s ability to get hold of their dollars if they keep them in Argentina, they prefer to send them abroad and, preferably, secretly.

As all economists know, or should know, the interest rate equilibrates the monetary markets. People deposit their resources in the local currency if the interest rates paid by these deposits compensate for the risks of having deposited them there and still produce a net yield similar to that they can get abroad in their standard of value, which is the dollar. Since the dollar is the standard of value, yields are compared with those in dollars. For example, if the rate of interest in the dollar market is 4% and the expected rate of devaluation of the peso versus the dollar is 6%, the Argentine banks would have to pay at least a little more than 10% (4+6) to convince people of depositing with them in pesos. Of course, there are other risks additional to currency devaluations. To compensate for these other risks (political risks or the risks of a poorly supervised banking system) for example) should be compensated by the Argentine banks to discourage capital outflows.[1] Well, the outflows appear when the risks and the interest rate are not high enough to compete with the yields of deposits in dollars in Uruguay, New York, or elsewhere. Thus, the more pesos the central bank prints, the more dollar reserves it loses.

Given the Argentinian experience with peso instability, you could think that the interest rates Latin American banks must pay to avoid capital outflows and even encourage inflows must be very high. No. As you can see in Graph 1, the deposit interest rates necessary to keep the Salvadoran financial markets stable and provoke capital inflows went down right after the 2001 dollarization from 6.5% to a level between 2 and 5%. If the market needs more resources, the additional demand for loans will raise the interest rates, and more money will flow from abroad. If you want less money, the interest rates will fall, and capital will flow out.

These rates have been high enough to keep the banks liquid even during the 2008 and the 2020 COVID crises. Today, the deposit interest rate is about 4.8%, which keeps the flows stable. Yet, in Argentina, the deposit rates in pesos averaged 85.68% and still could not keep the resources in Argentina. The country had a hemorrhage of outflows. The difference has nothing to do with the lack of legs in the dollars arriving in El Salvador. It is due to the trust that the dollar gives to depositors.

Of course, the low deposit rates result in low lending rates. The 2023 average lending rate in El Salvador was 5.57%. That of Argentina was 87.68% in 2023. A Salvadoran can get a 25- or 30-year mortgage at 6.5% in the local currency (the dollar). There is no way to get a long-term peso loan in Argentina, at least for ordinary people. So, the argument that dollarization would empty the banks because Argentines would take the dollars abroad doesn't work in a dollarized economy.

NOTE: The source of this and all other graphs is the IMF’s International Financial Statistics.

One of the arguments against dollarization in Argentina is that if you dollarize, you lose your ability to have monetary policy, which allows you (so they say) to keep the correct inflation rate by printing more or less of it. This sounds great until you realize that the interest rates in the dollar markets do this automatically and at interest rates much lower than those prevailing in the peso countries.

COMPARISONS BETWEEN NON-DOLLARIZED AND DOLLARIZED COUNTRIES

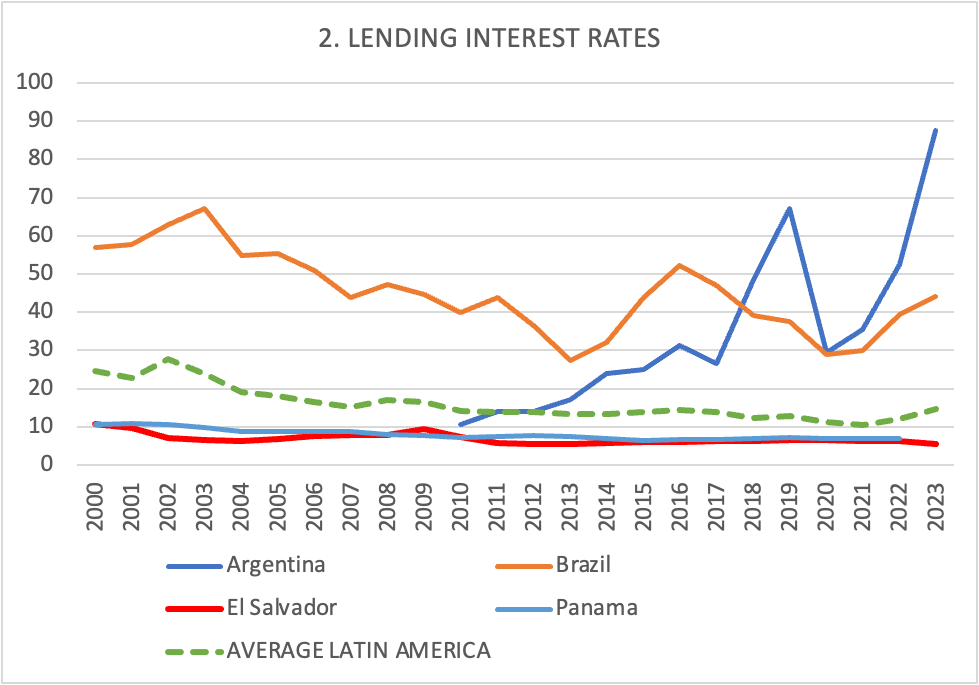

Following their argument, you would expect non-dollarized countries to need lower interest rates to equilibrate the markets. Yet, Graph 2 shows how the two dollarized countries, Panama and El Salvador, have lending rates much lower than those prevailing in the other Latin American countries.

The differences between the non-dollarized and dollarized countries’ lending interest rates are so vast that, if plotted in the same graph, they dwarf the differences between the average Latin American rates and the Salvadoran and Panamanian ones. For this reason, I compared such averages with the rates of the two dollarized countries in the International Financial Statistics data. For 2023, the Latin American average (14.72%) is more than twice El Salvador's (5.57%) rate. That means that, on average, Latin American borrowers have to pay more than twice the interest rates paid in dollarized countries to prevent capital from escaping from their countries. That is the difference between the pesos and the dollars. Of course, the interest rate is not the only variable affecting investment. But it makes a big difference. It tends to lower investment in non-dollarized countries.

The fact that the interest rate dramatically depends on the currency's stability can be better appreciated in countries where people can deposit in pesos and dollars. In all cases, the interest rate in dollars is much lower than in pesos. This difference is only attributable to the currency because all other risks are the same for the deposits in pesos and dollars—it is the same banks, the same country, the same government, etc. The only difference is the currency. And the public always requires lower interest rates to deposit their resources in dollars than in pesos in the banks of these countries.

COMPARISONS BETWEEN CURRENCIES IN THE SAME COUNTRY

Argentina

Notice the great difference between the lending rates in pesos and dollars in Argentina. This shows that people require lower yields to keep their deposits in dollars because the risks of this currency are much lower than in pesos.

In 2023, peso borrowers had to pay 87.68% on their loans, and those interests were still insufficient to stop capital outflow. Of course, the outflows were in dollars, but this was because nobody would take a deposit in Argentine pesos abroad, where they are not forced to. Thus, people exchange pesos for dollars and take away the dollars. But the currency they were escaping from was the pesos. The graph shows that the lending interest rate equilibrated the dollar market was 7.86%. Banks paid much less for deposits in dollars, not because they didn’t want dollars but because this was enough to attract the dollars they needed to lend them to their credit customers.

Now, we will see a series of graphs containing all the countries that publish their dollar interest rates with the IMF. In all cases, the interest rate in dollars was lower than in pesos.

Chile

Dominican Republic

Honduras

Paraguay

Uruguay

conclusions

The data shows that, as expected by theory, capital will stay where it receives higher yields once the risks of the operations are discounted. In Argentina, the capital leaves the country because the peso interest rates are too low to compensate for the loss of value of the peso. People know that if the government manages the currency, it will transfer the costs of its fiscal and monetary deficits to the depositors, holders of peso assets, pensioners, and salaried people with wages in pesos. This is what the Milei government is doing today. That is why the Argentine people are impoverishing at a pace and to an extent never before seen in the country.

People then take away their resources. To do that, they withdraw pesos from the banks, buy dollars, and send them abroad. The Central Bank creates more pesos to replace those that are withdrawn, increasing the inflation rate and devaluing the peso further, increasing the demand for exchanging pesos for dollars. This is the classic vicious circle of inflation produced by an accommodating central bank.

This vicious circle produces a mirage that is explicable in people not versed in economics but inexcusable in economists, who think that people trust the pesos (which retain their volume because the central bank is producing them) more than the dollars (which have a limited supply).

This is demonstrated by comparing the interest rates of dollars and pesos in the same country, where all the risks, except those associated with the currency, are the same. People depositing resources in Argentina run the same risks except the risk of the loss of value of the deposited currency. In 2023, on average, loans in dollars could be obtained at 7.86%, but in pesos, 87.68% does not cover the risk, and people take the money away.

As seen from the experience of all dollarized countries, this problem is automatically solved by dollarizing the economy and at meager interest rates.

Of course, you can always stabilize the economy through sheer Central Bank willpower not to create money unless it purchases foreign exchange for pesos. Argentina has not shown a propensity to exercise such willpower. But even if it did, Argentine investors would have to pay higher interest rates than needed. That is the price of keeping a currency—a lower investment.

This was the reason why El Salvador dollarized. The inflation rate was around 2%, and the country was one of the few investment-grade countries in Latin America (five, then reduced to two, Chile and El Salvador). But the lending rate of interest was too high, on the order of 20%. As shown in Graph 1, dollarization brought it down to about 6% on average. It was worth doing it.[2]

--------

Manuel Hinds is a Fellow at The Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise at Johns Hopkins University. He shared the Manhattan Institute's 2010 Hayek Prize. He is the author of four books, the last one being In Defense of Liberal Democracy: What We Need to Do to Heal a Divided America. His website is manuelhinds.com

[1] It is not exacty 10% but 10.24%, but 10% is close enough for a simple example.

[2] This material and the reasons why El Salvador dollarized is contained in Manuel Hinds, Playing Monopoly with the Devil: Dollarization and Domestic Currencies in Developing Countries, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2006.